Friday, May 4, 2007

Wednesday, April 25, 2007

Stories of Domestic Children

Senegal: Fatou Ndiaye is proud of herself Fatou left her birthplace Monbaye at the tender age of 7. The daughter of poor peasants, she was obliged to leave her family to seek a better life in town. Today, Fatou remembers the difficulties she faced when she first entered Dakar. "I came to the city in 1991. I was so small. I knew next to nothing. In the village I carried water, gathered wood. Work is very different here in town. I looked after babies, earning around 2,000 francs (US $3.60) a month. Sometimes I had kind employers; others beat me." By the age of 13, Fatou was an experienced domestic worker able to wash, sweep and iron. Aged 15, her monthly salary was more than 10,000 F (US $18). Employed in a home, she worked for an employer whom she considered kind. With her money, she provided for the needs of her mother and her two younger brothers. Sometimes she could even buy clothes for herself. And once a year, on the Festival of Tabaski, she returned to her village. Fatou also joined an association of young working women of Khadimou Rassoul, where held the post of Assistant Secretary General. Here she learned what her rights were, how to organise and how to give voice to workers. Her organisation, supported by the ILO and the non-governmental group ENDA Jeunesse Action, now has more than 300 members and has formed its own mutual insurance association through subscription. These funds help women when old age or maternity obliges them to set up their own income-generating activities (as employers prefer young women without children, believed to be more flexible). As part of an effort to provide some stability in their precarious working lives, the women have set up their own health insurance, taken literacy classes and, when possible, sought higher-paying work. The organisation has grown by stages. "We worked," says Fatou, "during all last year for four rights: the right to learn a trade; to read, to write; to organise; and the right to demand self-respect." These rights are starting to be recognised by employers. "They dare no longer mistreat us," she adds. Fatou also takes pride in their participation in the May Day parade. "This surprised everyone. No one had ever imagined that we had the ability to defend our rights, voice our complaints by acting out our daily lives, or access the media. We had this idea and the ENDA supported us." Fatou was also delegated by her comrades to participate in the International meeting of Child and Youth Workers of West Africa. Fatou concludes with a smile: "Now, I can be proud of myself."

Philippines: Gloria and the law that changed her life Gloria was only 13 when she entered employment as a domestic worker in the Philippine city of Pasig. All Gloria wanted was to save money so she could attend secondary school back home in the countryside. But this proved impossible when her mother, Chedita - who had just remarried - started taking 75% of Gloria's wage. Five months later Gloria was told to take care of an epileptic adult daughter of her employer. Already struggling to complete all the other domestic chores, Gloria was unable to cope with the sick woman. Her employers hit her for not taking proper care of their child. Gloria's beatings worsened following an incident when the epileptic woman fell and hurt herself during a seizure. A child, brimful of guilt and fear, Gloria faced her punishments in silence. This continued until one day Gloria's mother was horrified to witness her daughter being severely whipped. Chedita begged for the employers to release her daughter, but they refused. The beatings became more frequent. Then Chedita heard that the Philippines had passed a law that forbade child abuse and exploitation. Days after contacting social workers to explain her daughter's plight, Gloria was removed from her abusive employer. Before 1992, when the first comprehensive child protection laws were passed, a girl like Gloria may probably not have escaped her employer's abuses. But following campaigns by trade unions like the Federation of Free Workers and non-governmental organizations, national laws and children's lives are slowly improving. Chedita was too poor to take care of her daughter, so Gloria was placed in a rescue home run by the Visayan Forum, an ILO-supported organization that works with child workers. The rescue home provided her with shelter and counselling, and helped her file a criminal case against her former employers.

Guatemala: A new life for Santa Eva Santa Eva was found when she was only 12 years old by the facilitator of the Conrado de la Cruz Association action programme against child domestic labour. The Conrado de la Cruz Association works in collaboration with the International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) on the prohibition of and immediate action for the elimination of the worst forms of child domestic labour. Before joining the action programme, Santa had done all kinds of work. She went from working in a tortilla bakery to packing vegetables for export, then to domestic work in a private home. After a long and difficult year working, her health began to deteriorate. When the facilitator included her in the group, Santa found it difficult to take part. However, as she talked with the team of facilitators on the action programme, the reason for this behaviour emerged. Santa was unhappy at being separated from her parents and family. When Santa's mother left her father, she abandoned Santa and her three younger brothers to marry another man and start a new family. It became necessary for Santa to find work immediately in a private home to feed and care for her three brothers. The facilitators and the girls in her group played the role of advisors. Santa was able to pour out her heart to them about the "torture" of seeing her mother who lived only two blocks away with her new family while she and her brothers were abandoned. At times, she saw her mother in the market and was mistreated when she tried to speak to her. The action programme provided Santa with a new living environment. Speaking of her life helped Santa to come to terms with her difficult situation, as she realized that most of the other girls shared many of her experiences and they all had to struggle to find other options. "The objective of the Conrado de la Cruz Association is to support and to contribute to the elimination and prevention of child domestic labour, specifically involving girls from rural areas of the city", says Julián Oyales, Director of Conrado de la Cruz and coordinator of the ILO/IPEC action programme. Santa has also recovered her physical and mental health through this programme, as well as being able to study and have hope for the future. She was able to finish her primary education through the action programme. She was interested in working in health and continued to study to be a nursing assistant. Santa's participation in Conrado de la Cruz has given her a new dimension and outlook on life. Santa has impressive leadership qualities and skills when it comes to identifying other girls in her community who are suffering as she did. This is because she knows the area where she lives like the back of her hand and quickly recognizes other girls in risk situations. As a programme presenter she has joined the cause of Conrado de la Cruz and has been able to rescue girls who have had to work because their families have abandoned them or are desperate. Today, Santa is 15 years old and she works for the association as a group presenter, participates in classes at the Education Centre, has done a computer course and is studying to be a nursing assistant. Once a victim herself, Santa now works to help others.

ILO: International Labour Organization

Child Labour in Pakistan by Jonathan Silvers

Pakistan has recently passed laws greatly limiting child labour and indentured servitude—but those laws are universally ignored, and some 11 milion children, aged four to fourteen, keep that country's factories operating, often working in brutal and squalid conditions ..... No two negotiations for the sale of a child are alike, but all are founded on the pretense that the parties involved have the best interests of the child at heart. On this sweltering morning in the Punjab village of Wasan Pura a carpet master, Sadique, is describing for a thirty-year-old brick worker named Mirza the advantages his son will enjoy as an apprentice weaver. "I've admired your boy for several months," Sadique says. "Nadeem is bright and ambitious. He will learn far more practical skills in six months at the loom than he would in six years of school. He will be taught by experienced craftsmen, and his pay will rise as his skills improve. Have no doubt, your son will be thankful for the opportunity you have given him, and the Lord will bless you for looking so well after your own." Sadique has given this speech before. Like many manufacturers, he recruits children for his workshop almost constantly, and is particularly aggressive in courting boys aged seven to ten. "They make ideal employees," he says. "Boys at this stage of development are at the peak of their dexterity and endurance, and they're wonderfully obedient—they'd work around the clock if I asked them." But when pressed he admits, "I hire them first and foremost because they're economical. For what I'd pay one second-class adult weaver I can get three boys, sometimes four, who can produce first-class rugs in no time."

The Atlantic online

Children Set Another Milestone!

The Global March is once again overwhelmed with the monumental success of the Children's World Congress, Florence. Though we were all angry at the imposed absence of many of our young child participants from Africa and Asia, the strong vibrant and passionate voice of the children who participated as well as the committed response from the adults lifted our spirits and hopes and brought forth unprecedented enthusiasm and encouragement towards a better future for the children the world over. It's not often that history witnesses its making by children from all parts of the world including former slaves engaged in most hazardous occupations alongside those children who study in good schools and are aware and committed in their fight against child labour. They could very well empathise and understand the difficulties of exploitation, miseries and agonies of child labourers. These children were strongly supported in their endeavour by the world leaders including the ministers from rich and poor countries, the senior officials of UN agencies and the key functionaries of international trade union movements and civil society organisations in Florence from 10-13 May. The four days of the Congress culminated in a massive march through the streets of Florence from Piazza della Signoria to Piazza Santissima Annunziata. Thousands of adults and children took part in the march and were carrying banners and colourful posters for ending child labour and providing education to all. The atmosphere was resplendent and enlivened with chanting of slogans and rhythmic beats of drums. The most important and innovative moment of the Congress was the accountability session. It was actually beyond everyone's expectations. The children had no bias, prejudice, shyness, fear or hesitation in raising all their questions to the world leaders, which an adult would fail to do with the same amount of honesty and clarity. Each and every detail was minutely discussed. Again, the children's questions showed that they have a very clear understanding of international politics and that they can bring new perspectives in the struggle against child labour. They also stressed their own commitment in creating a world free of child labour. They said, “ We must work at the national level and establish a Children's Parliament, in every country, that is not just a symbol but a source of power for children to change the situations that we think are wrong. This Parliament would elect a representative to the country's government.”

Global March Against Child Labor

Peace and justice. The Global Economy Promotes Child Labour by David Bacon.

SAN FRANCISCO (5/28/96) -

The face of the global economy is increasingly the face of a child. It's not a child at play, or studying in school. It is the face of a child at work. In recent months, two international conferences have pulled away some of the veils hiding this face. One, ironically, was the gathering of bankers and industrialists in Davos, Switzerland in January, a group described by New York Times correspondant Thomas Friedman as "the ultimate capitalist convention." The other meeting brought together labor organizers, human rights activists and advocates for children in Mexico City - the Second International Independent Tribunal Against Child Labor. When two organizations, with such diametically opposed visions of the world, see the same danger, its reality is hardly debatable. The Davos World Economic Forum brings together the political figures and financial elite who write the trade deals, manage institutions like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, and design the economic rules of life for most of the world's people. Instead of celebrating the spectacular growth of transnational corporations and banks, however, and their continuing integration of the world's economy, the founder and managing director of the Davos forum speak fearfully of the future. "Economic globalization has entered a critical phase," predicted Klaus Schwab and Claude Smadja, in an essay published on the conference's opening day. "A mounting backlash against its effects, especially in the industrial democracies, is threatening a very disruptive impact on economic activity and social stability in many countries." In Mexico City two months later, witnesses from 18 countries condemned the growing labor of children worldwide as the most dramatic consequence of that economic globalization, and a principal cause of the backlash feared in Davos. Doris Crosby, secretary-general of the General Confederation of Workers, one of Peru's largest union federations, shocked participants when she announced that the number of working children had grown from 500,000 in 1993, to 1.5 million just two years later. She quoted census figures compiled by the Peruvian government itself. "We're going from being a civilized country in the third world to a new, fourth world," she said. Crosby blamed privatization programs for much of the increase. "Once a business has been privatized," she explained, it goes through a phase of getting rid of the people who work there. Then these same businesses rehire workers, but at the minimum monthly wage of 132 soles, with no pensions, benefits, unions or rights. Parents can't possibly support a family on this wage, so they have to tell their children to go to work." The Peruvian government's poverty line is set at 426 soles. Peru's working children catch fish with their parents, work in mines, go out to the fields to harvest crops, bake bread, and sell candy in the streets. "Little children come up to women in the market and ask to carry their bags, which are much too heavy for them to even lift," she recounted despairingly. Privatization of government enterprises has affected hundreds of thousands of workers in Peru. The letter of intent, signed by Peru's President Alberto Fujimori in order to receive loans from the International Monetary Fund, spells out the economic policies of the government, including the amount of privatization, according to Crosby. Almost every witness at the Mexico City tribunal described the same experience with privatization programs. They are one of the most common conditions for loans from the IMF and the World Bank, providing increased investment opportunities for domestic and international corporations. In the last six years in Mexico, hundreds of thousands of jobs have been eliminated by privatization. Here too the number of children in large cities who not only work in the streets, but live in them, has grown rapidly. Emilio Krieger, the dean of Mexican labor attorneys, estimates that 15 million children work in Mexico.

Peace and Justice

http://dbacon.igc.org/PJust/14ChildLabor.htm

Child domestics are the world's invisible workers because the types of works are often hidden away: it's not in industrial sector but in subsistence agriculture, household and urban informal sectors.

SO, DO YOU THINK LIKE M. FRIEDMAN, THE ECONOMIST, THAT THE ABSENCE OF CHILD LABOR IS A LUXURY THAT MANY POOR STATES CANNOT AFFORD??

Tuesday, January 30, 2007

Punishments

Here is an article on the punishments incurred by the employers of children in Benin.

Let us take the case of Benin in Black Africa. Benin is the moving plate of children's traffic. Indeed, certain families which can not put their children in schools for lack of means, entrust their children to "boatmen" who say to them educators and who are in fact children traffickers . And so for 15 in 20€ the parents believe to give a future to their children.

These children are resold in fact to big developers: cocoa plantations, sugar cane plantations in Cameroon, in Côte d'Ivoire, in the Gabon...

It is fir it that Benin makes decisions of justice against these traffickers:

10 - 20 years of reclusion, and criminal reclusion with perpetuity if rapes, violence or also ill-treatment. The traffickers do not escape to pay fines between 760€ and 7600€.

Let us take the case of Benin in Black Africa. Benin is the moving plate of children's traffic. Indeed, certain families which can not put their children in schools for lack of means, entrust their children to "boatmen" who say to them educators and who are in fact children traffickers . And so for 15 in 20€ the parents believe to give a future to their children.

These children are resold in fact to big developers: cocoa plantations, sugar cane plantations in Cameroon, in Côte d'Ivoire, in the Gabon...

It is fir it that Benin makes decisions of justice against these traffickers:

10 - 20 years of reclusion, and criminal reclusion with perpetuity if rapes, violence or also ill-treatment. The traffickers do not escape to pay fines between 760€ and 7600€.

Monday, January 22, 2007

"Chocolate for children..."

A lot of children works in the world, even if every child who work is a serious problem, some examples are more impressive than others, these can help us to understand how complex this problem can be, and realize that in a lot of situations child labour is just an element of a huge mechanism. And at the end of this mechanism we can often find people like me or you : consumers…

Children like chocolate and it is well known that chocolate brings joy to them… but on the other side of the earth the situation is totally different, some children don’t know the chocolate as a delicious dish but as an object of torture and as an obstacle to their rights of children. Even if “torture” is quite a violent word, it is the best word to describe what they suffer (physical and psychological injuries).

Let’s see some numbers which help us to understand the extent of this problem. In 2001, some us organisations ( governmental and non governmental) underlined this phenomenon. According to theirs results more than 100.000 children work in chocolate production in Ivory Coast ( which is the bigger cocoa producer with a part of 43% in the world production).

Children like chocolate and it is well known that chocolate brings joy to them… but on the other side of the earth the situation is totally different, some children don’t know the chocolate as a delicious dish but as an object of torture and as an obstacle to their rights of children. Even if “torture” is quite a violent word, it is the best word to describe what they suffer (physical and psychological injuries).

Let’s see some numbers which help us to understand the extent of this problem. In 2001, some us organisations ( governmental and non governmental) underlined this phenomenon. According to theirs results more than 100.000 children work in chocolate production in Ivory Coast ( which is the bigger cocoa producer with a part of 43% in the world production).

After a period of great mediatisation of this problem and the pressure of public opinion, a compromise was signed by some us chocolate companies to eradicate this kind of practices by 2005 ( via the Harken-Engel Protocol )…

But two years later, the problem hasn’t been solved. In the bigger chocolate producers countries like Ivory Coast or like Ghana , child slave labour is still an important phenomenon…

To go into detail of this problem please visit :

http://www.american.edu/ted/chocolate-slave.htm

But two years later, the problem hasn’t been solved. In the bigger chocolate producers countries like Ivory Coast or like Ghana , child slave labour is still an important phenomenon…

To go into detail of this problem please visit :

http://www.american.edu/ted/chocolate-slave.htm

Friday, January 19, 2007

Actions against Child Labour: the role of governments and organisations

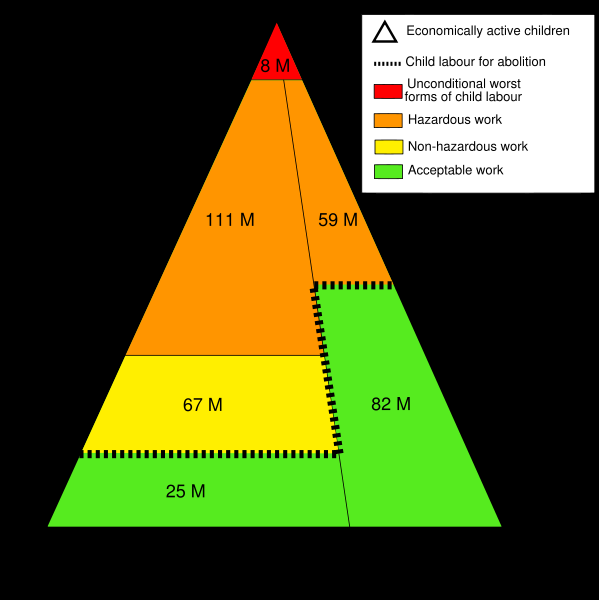

It’s estimated by the international Labour Organization that 250million children between 5 and 14 work in developing countries, 120 million on a full time basis. They work mainly in agriculture, as domestics, in manual trade and services, in manufacturing and constructions.

The main reason for working is that the family doesn’t earn enough money and they have to help in this objective. Work isn’t necessarily wrong in a child growing up, it can be a positive experience… but only if he’s free to do it, if he works in good conditions, if the education isn’t denied and if he has the pay that he deserves.

Unfortunately children in this case are rare compared to the other who work in very bad conditions, using dangerous substances and materials, who are beaten, reduced to slavery, forced to work… and so on. We could enumerate a lot of situation which go against the children’s rights.

What can be done in order to help those children?

Firstly, we can say that the governments have to act by promulgating laws against Child Labour and to make it respected. However it is more difficult in poor countries where it is contributing to maintain the economy. Their work isn’t only important for the family but also for their country! Nevertheless, governments have to prohibit it for the welfare of the population . The have to ratify the ILO Convention n°182 to eliminate the worst forms of child labour. Today 163 countries have ratified this convention. Another convention is interesting because it specify the minimum age and the country can choose it in accordance with the economy and other factors.

Secondly, there are a lot of organizations around the world which act against child labour around the world. For example : UNICEF, Global March, the child Labor Coalition…and many others. ILO (International Labour Organisation) is acting against child labour worldwide. In many countries they are setting up programs : International Programs on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPECL). Governments and organisations can act together for a better efficiency.

For Example in Nepal where 41% of the children from 5 to 14 are working in agriculture, manual trade and industrial sector. They act with the government and today more than 100 programs and mini programs have been implemented in Nepal.

The main reason for working is that the family doesn’t earn enough money and they have to help in this objective. Work isn’t necessarily wrong in a child growing up, it can be a positive experience… but only if he’s free to do it, if he works in good conditions, if the education isn’t denied and if he has the pay that he deserves.

Unfortunately children in this case are rare compared to the other who work in very bad conditions, using dangerous substances and materials, who are beaten, reduced to slavery, forced to work… and so on. We could enumerate a lot of situation which go against the children’s rights.

What can be done in order to help those children?

Firstly, we can say that the governments have to act by promulgating laws against Child Labour and to make it respected. However it is more difficult in poor countries where it is contributing to maintain the economy. Their work isn’t only important for the family but also for their country! Nevertheless, governments have to prohibit it for the welfare of the population . The have to ratify the ILO Convention n°182 to eliminate the worst forms of child labour. Today 163 countries have ratified this convention. Another convention is interesting because it specify the minimum age and the country can choose it in accordance with the economy and other factors.

Secondly, there are a lot of organizations around the world which act against child labour around the world. For example : UNICEF, Global March, the child Labor Coalition…and many others. ILO (International Labour Organisation) is acting against child labour worldwide. In many countries they are setting up programs : International Programs on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPECL). Governments and organisations can act together for a better efficiency.

For Example in Nepal where 41% of the children from 5 to 14 are working in agriculture, manual trade and industrial sector. They act with the government and today more than 100 programs and mini programs have been implemented in Nepal.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)